Robinson spent a night in jail on a contempt of court charge.

The seat had been held by Billy Robinson Jr., a Democrat, for 20 years his father had held it before him. At the urging of local Republicans, she ran in 2001 for the House of Delegates in a majority Black district in Norfolk. Sears, then a married mother of three who had run a homeless shelter and gone to graduate school, began her political career. More than a dozen years passed before Ms. When she listened to the 1988 presidential campaign, hearing the debates over abortion and welfare, she realized, to her surprise, that she was a Republican. She already had plenty of life experience by that point: moving at the age of 6 from Jamaica to the Bronx to be with her father, who had come seeking work joining the Marines as a lost teenager and learning to be a diesel mechanic becoming a single mother at 21. Sears dates her own partisan epiphany to her early 20s. “And who better to help make that change but me? I look like the strategy.” “The only way to change things is to win elections,” she said. Sears insists that many Black and immigrant voters naturally side with Republicans on a variety of issues - and that some are starting to realize that. Sears won with typical Republican voters in an especially Republican year. Democrats say there is little evidence for the latter, and that Ms. Sears embodies: whether she is a singular figure who won a surprise victory or the vanguard of a major political realignment, dissolving longtime realities of race and partisan identification. “But the messenger is equally important.” Sears, 57, said over a lunch of Jamaican oxtail with her transition team at a restaurant near the State Capitol. Sears’s triumph, in news profiles and in the post-election crowing of conservative pundits, has been on the rare combination of her biography and politics: a Black woman, an immigrant and an emphatically conservative, Trump-boosting Republican. Senate, but this earned her little beyond a few curious mentions in the press. She briefly surfaced in 2018, announcing a write-in protest against Virginia’s Republican nominee for U.S. The political trajectory that preceded it was hardly more auspicious: She appeared on the scene 20 years ago, winning a legislative seat in an upset, but after one term and a quixotic bid for Congress, disappeared from electoral politics. Her campaign was a long shot, late in starting, skimpily funded and repeatedly overhauled. That she was standing here at all was an improbability built upon unlikelihoods. Then, a clerk said, pointing to the giant wooden gavel at Ms. Sears followed along as the clerks explained arcane Senate protocols, though she occasionally raised matters that weren’t in the script. It was empty but for a few clerks and staffers who were walking her through a practice session, making pretend motions and points of order.

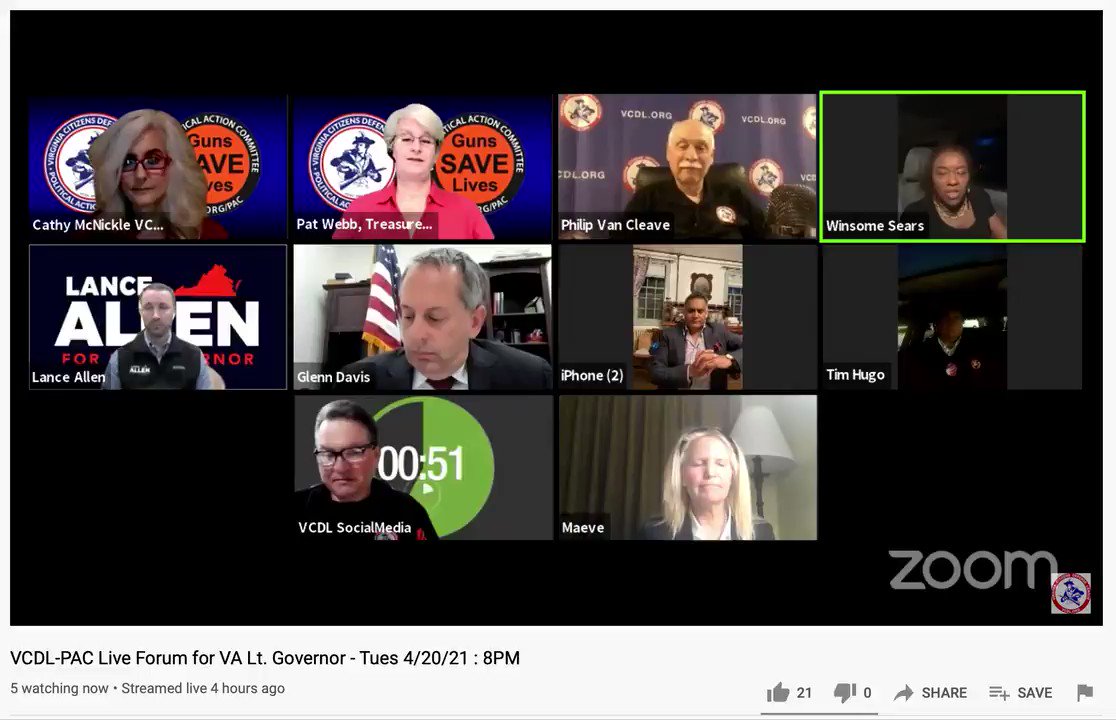

On a December afternoon, Winsome Sears, Virginia’s lieutenant governor-elect, stood at the podium in the State Senate chamber where she will soon preside.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)